At 1 x speed, this post is seven minutes long. I thought about the material and wrote it over several years.

I had drinks with a sixty-year-old attorney who said he had never made a mistake with a client. I tried to be polite for a few minutes and asked him to say more. He said that he had worked for thirty-five years and he never had a bad result or even missed a deadline. I listened for a while, wondering—did he believe what he was saying? I realized I was either sitting with a narcissist who had little self-awareness or more likely a sociopath trying to see how gullible I was. I walked out in the middle of a sentence and never looked back.

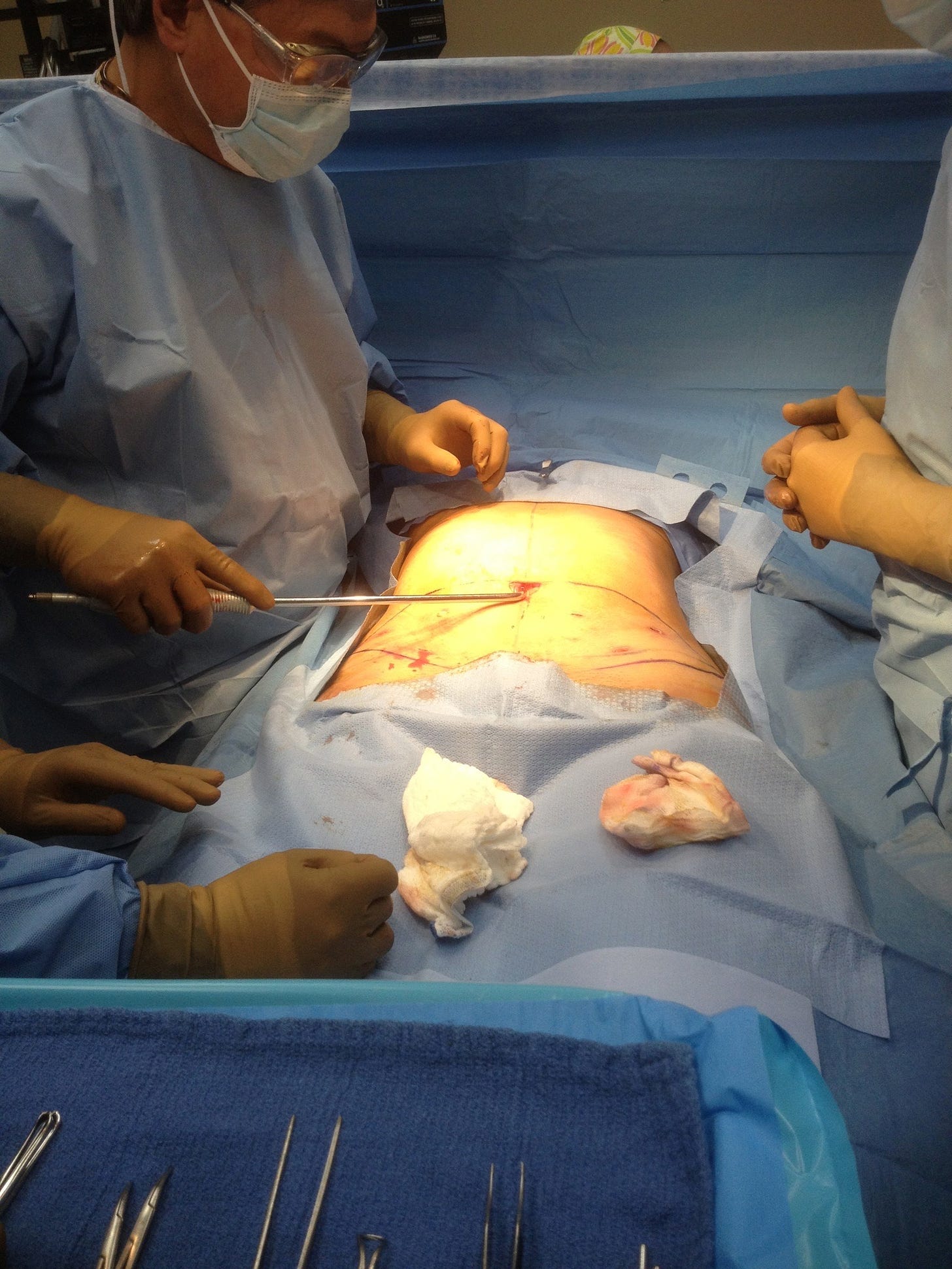

WE SURGEONS are continually reminded of our errors, sometimes by lawyers who specialize in suing us. We make hundreds of decisions every day, and we understand the risks of a mistake. Although most of these are neither consequential nor result in damage, all of us have seen patients injured, and many of us worry constantly. For example, ophthalmologists have a blinding or two during their careers, and general surgeons have a few fatal and near-fatal cases every year. No one can predict when disasters will come, and good surgeons never consider themselves completely blameless.

Studies of liposuction surgeons show that they puncture their patients’ internal organs about once every 3,000 cases. In some areas of the body, changing the angle of the suction cannula by fifteen (15) degrees can do it. Some of these cases are serious and about ten percent die. Others are never noticed. Since a typical lipo requires two thousand strokes of the instrument, surgeons who have performed 1000 cases have performed two million cannula strokes. Perfect coordination and consistency are impossible with these numbers.

Patients sign documents saying that complications and death are possible, but who expects anything to happen? No one wants to hear about that paperwork when they are in the hospital after they had their bowel repaired. I know doctors who will swear under oath (for a price, of course) that punctures are malpractice and that they should never happen. We performed over 10,000 liposuction cases in my surgical centers, and I have seen this problem several times. Fortunately, none of my patients ever died from this.

I often meditate about the following. Hippocrates told us to do no harm, but risk is everywhere. A doctor’s job is to cautiously exchange medical hazards for the best chance of improvement. We must take full responsibility in an era when bad outcomes are inevitably viewed as malpractice.

CLIMBERS ARE exposed to dangers as well. Our safety rules are simple-minded, but just like surgeons, we are imperfect. For example, no amount of checking cuts your chance of tying a bad knot to zero or guarantees that you will tie that knot at all.

I once climbed to the top of a 100-foot rock using a rope but without a “belayer” holding it for me (I was “rope soloing.” These techniques are beyond the scope of this article.) I then tied a knot at the anchor that I had used thousands of times before. I made a mistake:

I then slid back down the rope using a “Grigri” friction device on the left-hand strand. If I had used the right-hand rope, I would have died right then. After I got to the bottom, I climbed back up the rock using the rope as a safety but without putting my weight on it. When I was once more at the top, I realized that the knot was not secure and that I could have killed myself. I was shaken but had to presence of mind to tie in and take the photo. But since I didn’t slip, I thought, “No harm, no foul.” I fixed it and carried on.

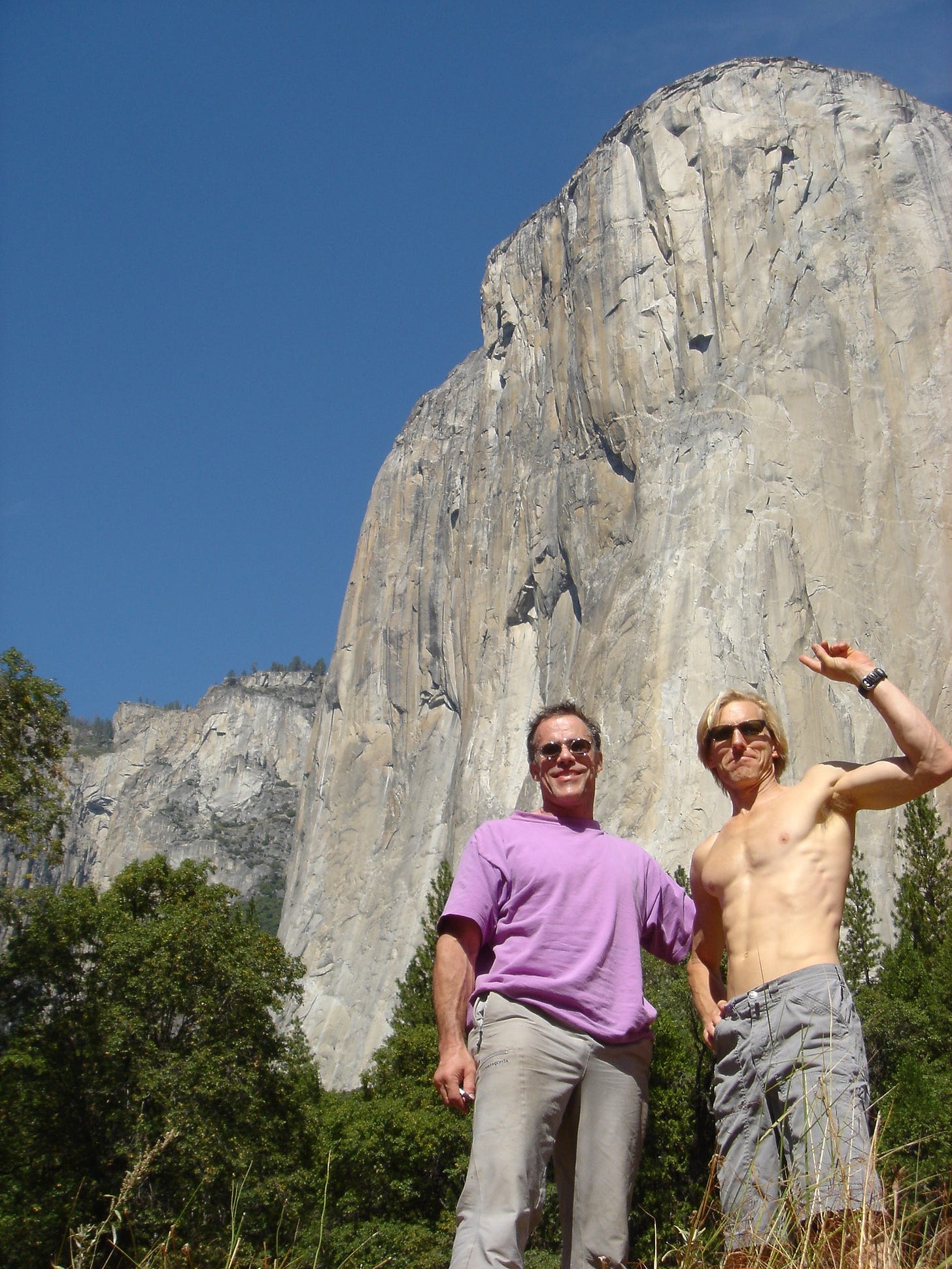

Here is another example that had consequences. I was on a speed ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan (for me, this was less than 24 hours). I was climbing despite crippling professional stresses (error 1). My partner convinced me against my better judgment to only bring one long rope instead of two (mistake 2). He got ahead of me and used too much rope (error 3), so when I had to do a maneuver called a pendulum, I tried to do it without enough extra rope at my end (mistake 4). I slammed into the rock and broke my foot.

We rappelled down, and I crawled a mile to the road. When I went to see my orthopedist the next week, he cast my foot but did not refer me to a foot specialist (mistake 5).

He told me to wait three months, and I listened to him instead of getting another opinion (mistake 6). The specialist told me later that waiting caused improper healing. If I had seen him within ten days, he would have repaired the problem, and I would have been fine. This string of six errors resulted in a permanent injury that does not allow a lot of hiking and sings to me daily.

I climbed many dozens of times a year when I was active. I was careful, even paranoid, and worked on my skills, so I prevented thousands of mishaps. For example, I recognized and avoided loose holds. While climbing easy ground without a rope, I slipped on wet rock but caught myself. And I once avoided falling 40 feet by screaming STOP to my belayer. He had nearly let my belay rope slide through the device he was holding. With so many experiences like these, I gave little thought to mistakes that did not result in harm. But once in many hundreds of days of climbing, fatigue or a small distraction causes an accident.

Never fall prey to thinking that training, ritual, and careful technique will prevent all calamities. These help, but something will eventually get you if you expose yourself to life’s risks. Unexpected events are inevitable. For climbers, for surgeons, for all of us, errors are the price we pay for what we do. Do not fool yourself—it will happen to you.

Be careful out there.

Share this post